In 1952, after Medgar’s graduation and after Myrlie’s sophomore year, the couple settled in Mound Bayou, an all black town in the Mississippi Delta. Medgar became an insurance agent for Magnolia Mutual Insurance, one of the few black-owned businesses in Mississippi where a young black person could get a decent job.

Dr. T.R.M. Howard, founder of the company, also founded an organization called the Regional Council for Negro Leadership. Medgar became active with this group and deeply involved with poor black people.His travels as an insurance agent gave him a close, first-hand look at their conditions, convincing him that more had to be done for black sharecroppers. (1)

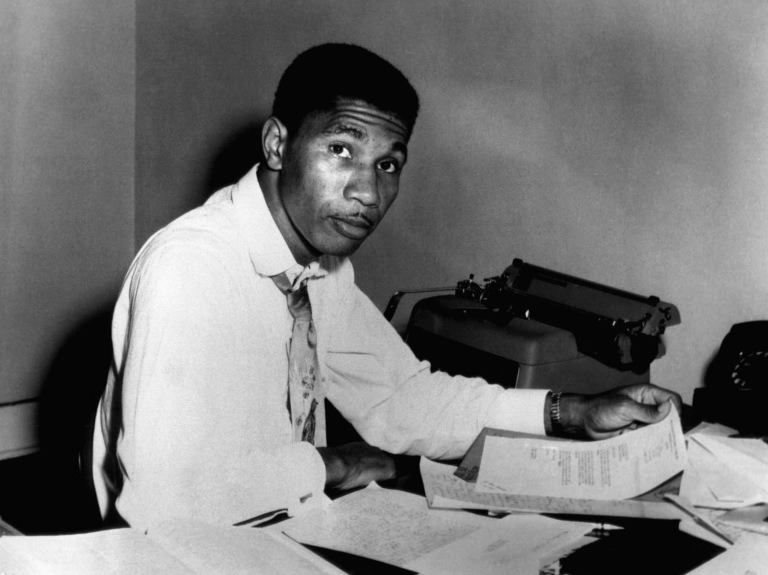

Medgar Evers and NAACP

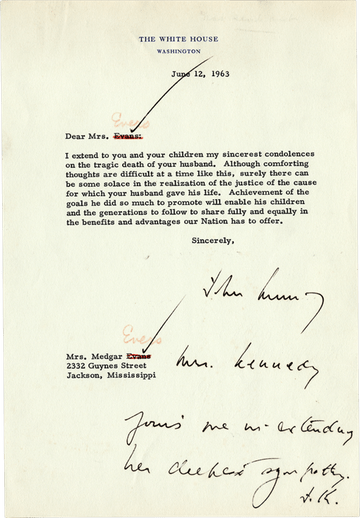

Medgar Evers was the first NAACP field secretary in Mississippi. The civil rights leader was killed in 1963.

Medgar Evers was the first NAACP field secretary in Mississippi. The civil rights leader was killed in 1963.

It was largely because of Howard’s influence that Evers, from 1952 to 1954, not only traveled his Delta route selling insurance, but organized new chapters of the NAACP. The NAACP organizing travels convinced Evers that Jim Crow rendered the state a virtual closed society and that mobilizing at the grassroots level was essential for building a movement for social change. Increasingly, too, Evers saw himself in the vanguard to put an end to Mississippi’s infrastructure of segregation. Other people in the still-young Mississippi Civil Rights Movement also began thinking of Evers as a leader.

E.J. Stringer, president of the NAACP Mississippi State Conference, was so impressed with Evers’s leadership potential that he recommended him for the newly created position of state field secretary of the civil rights organization. The National Office of the NAACP voted in favor of Stringer’s recommendation.

When Evers assumed his position as state field secretary, he began an eight-year career in public life that was both demanding and frustrating. The 1950s proved frustrating and anxiety-laden as some white Mississippians responded with massive resistance to the civil rights activities of the NAACP and to the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka decision which declared segregated schools unconstitutional. There was widespread racial violence against blacks and from 1955 to 1960, Evers faced a range of daunting challenges. He investigated nine racial murders and countless numbers of alleged maltreatment cases involving black victims during the period. (2)

Medgar Evers did a lot to bring the NAACP to Mississippi. But one of his main contributions was to take news of the struggle in Mississippi to the people of the U.S. and the world through news releases, interviews, and speeches. (1)

Struggle to Desegregate Higher Education

Medgar Evers helped James Meredith in his effort to enroll at the University of Mississippi in 1962. He secured the NAACP’s legal team headed by Thurgood Marshall, who had won the Brown v. Board of Education lawsuit, to assist Meredith. Evers himself had been denied admission to Ole Miss law school in 1954.

The town of Oxford erupted. It took some 30,000 U.S. troops, federal marshals and national guardsmen to get James Meredith to class after a violent campus uprising. Two people were killed and more than 300 injured. Some historians say the integration of Ole Miss was the last battle of the Civil War. (Read more)

Campaign Against Racist Brutality

Between 1889 and 1940, almost 3,100 black people were lynched in the U.S., mostly in poor rural areas of the South. The use of violence and terrorism for purposes of social control continued in Mississippi in the 1950s and the 1960s. Medgar was on the frontline in investigating many of these attacks, and publicizing them before the eyes of the nation. He often disguised himself as a poor sharecropper, changed cars in different locations, and visited areas late at night in order to get evidence about violent incidents. (1)

We are concerned about the fact that the lynchers of Mack Charles Parker are known to the F.B.I. and state officials. However, despite this knowledge not a single person has been arrested, which raised this question: is it excusable to lynch a person to death and inexcusable to murder one? For when one is murdered, the guilty is immediately pursued, and if apprehended, arrested. But not so with lynchers. They are still free, though they are known.

Struggle for Voting Rights

Upon returning home after World War II, the initial “fight” for Evers was to register to vote. For Evers voting was an affirmation of citizenship. Accordingly, in the summer of 1946, along with his brother, Charles, and several other black veterans, Evers registered to vote at the Decatur city hall. But on election day, the veterans were prevented by angry whites from casting their ballots. The experience only deepened Evers’s conviction that the status quo in Mississippi had to change. (2)

The Right to Vote in Mississippi

At the time John F. Kennedy takes office in January 1961, a person trying to register to vote in Mississippi must first pass a literacy test, then explain a portion of the US Constitution, and also be able to pay a poll tax before voting. While poor educational opportunities and overt racial discrimination by registrars make it difficult for many blacks to meet all of these requirements, terror, violence, and economic intimidation also suppress black voter participation. In 1955, two civil rights workers active in voter registration were murdered. (Read more)

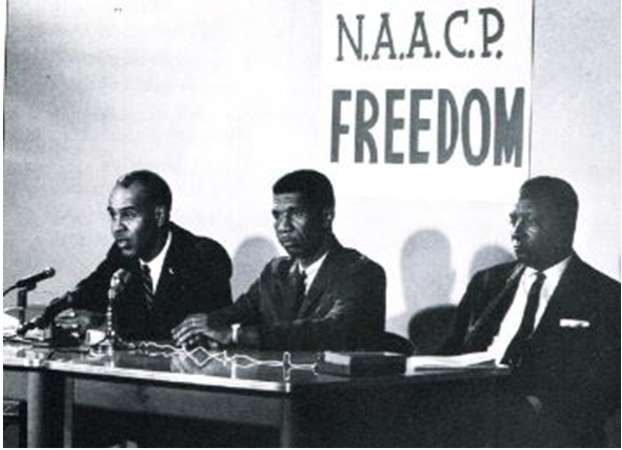

Medgar Evers on Television

Mass demonstrations by students and young people against Jim Crow segregation broke out again in Jackson in early 1963. When the Mayor went on television to call for an end to the protests, Medgar Evers appealed to the FCC [Federal Communications Commission] under the “equal time” provision and won 17 minutes to publicly make the case for integration and equal rights—a first in Mississippi history. On May 28, while speaking at a local AME church, he called for a “massive offensive against segregation.” And on June 1, 1963 Medgar and NAACP national executive secretary Roy Wilkins were arrested on a picket line at a Woolworth’s store in Jackson. (Read more)

Featured image: a still from CBS News video

(1) Bailey, Ronald W. Remembering Medgar Evers … for a New Generation. Oxford, Miss.: Distributed by Heritage Publications in cooperation with the Mississippi Network for Black History and Heritage, 1988.

(2) Davis, Dernoral. “Medgar Evers and the Origin of the Civil Rights Movement in Mississippi.” Mississippi History Now, http://mshistorynow.mdah.state.ms.us/articles/53/medgar-evers-and-the-origin-of-the-civil-rights-movement-in-mississippi. Accessed 28 September 2016.